let's say we have a business that manages peer to peer payments, and we are writing a program responsible for updating the status of a given user in the system:

data class UpdateUserStatusPayload(

val userId: Long,

val newStatus: UserStatus

)

class UserStatusManager(private val userRepository: UserRepository) {

fun updateUserStatus(payload: UpdateUserStatusPayload) {

userRepository.getUser(userId)?.let { user ->

user.status = payload.newStatus

}

}

}

this code snippet is very straightforward and does two things:

- retrieves the user from the database

- if the user exists, updates its status with the

newStatusfrom theUpdateUserStatusPayload

the beauty of the orchestrator model

but what if you want to perform side effects? say some downstream consumer also needs be notified of this status change - for example a user audit service responsible for storing all changes made to Users in our system, which is isolated from the current codebase and managed independently. you have 2 real choices to support this: extending the existing UserStatusManager or introducing the orchestrator model. the former will result in violation of the single responsibility principle, so it makes sense to go with the latter.

when you have a system with many different functionalities, you often need to break up each functionality into small, modular components. their modularity makes them resuable, independently testable, and significantly easier to maintain. this works at a system design level, where you might have multiple services that are independently responsible for sub-parts of an overall piece of a functionality, but also works at the code implementation level.

in our example, we want to extend the user status update functionality to fire off an event (let's say a Kafka topic called UserUpdateTopic). using the orchestrator model, this could look like:

fun UserStatusUpdatePayload.toKafkaMessage(): UserUpdateTopic {

// some serialisation implementation

}

class UserStatusUpdateOrchestrator(

private val userStatusManager: UserStatusManager,

private val userUpdatePublisher: KafkaPublisher<UserUpdateTopic>

) {

fun performUserStatusUpdate(payload: UserStatusUpdatePayload) {

userStatusManager.updateUserStatus(payload)

userUpdatePublisher.publish(payload.toKafkaMessage())

}

}

reusuability

if i wanted to publish user updates elsewhere in the codebase, i can. if i want to publish user status updates elsewhere in the codebase, i can. whether that's functionally a good idea or not is up to the implementer, but the point stands that each action performed is now technically independent of eachother.

independent testability

all 3 units of code in question are independently testable now:

- i can write a test that checks my orchestrator calls

userStatusManager.updateUserStatus, and then callsuserUpdatePublisher.publish - i can write a test that checks the status manager updates the user status (if the user exists)

- i can write a test that checks the status manager does nothing (if the user doesn't exist)

- i can write a test that checks the update publisher publishes to the correct topic (or whatever)

notice none of the tests depend on any of the functionality being shared or some action from another unit happening first? this is true independence and proper functional isolation

easier to maintain

say the implementation of the UserStatus changes, causing the userStatusManager.updateUserStatus logic to change, by introducing the orchestrator model, we don't need to change the implementation of the orchestrator nor the publisher.

sealing the deal with sealed classes

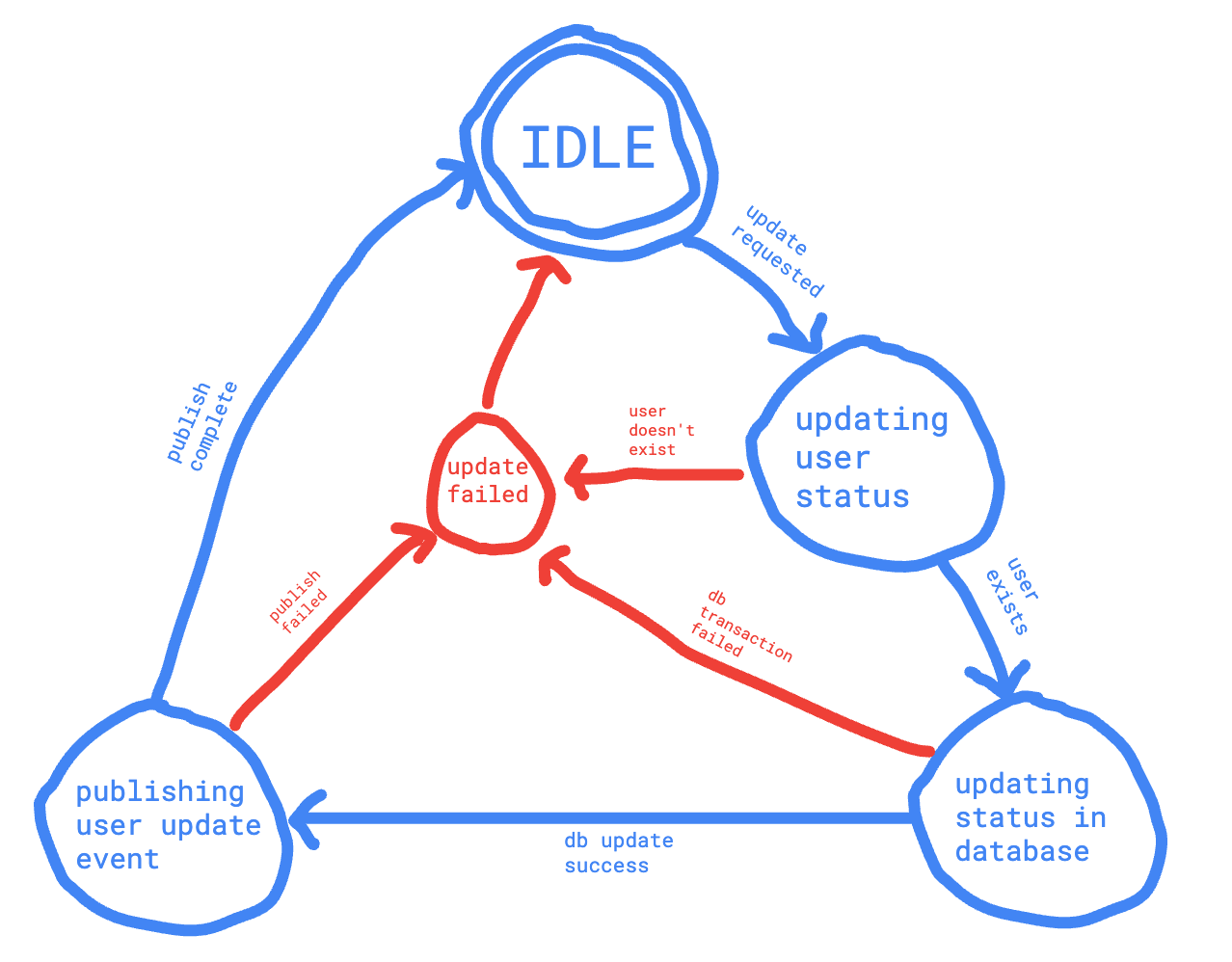

in reality, the orchestrator model is best used with a finite state machine. a finite state machine in principle is an object or piece of logic that transitions between a fixed set of states based on events that occur in the system and conditions for those events. our user status update functionality as a state machine could look like:

to properly implement this with the orchestrator model in kotlin, we can use sealed classes to represent our compile-time finite states. let's refactor our approach:

sealed interface UserStatusUpdateResult

object UserStatusUpdateSuccess : UserStatusUpdateResult

object UserStatusUpdateFailure : UserStatusUpdateResult

class UserStatusManager(private val userRepository: UserRepository) {

companion object {

val logger = logger()

}

@Transaction

fun updateUserStatus(payload: UpdateUserStatusPayload): UserStatusUpdateResult {

try {

val user = userRepository.getUser(userId) ?: return UserStatusUpdateFailure

user.status = payload.newStatus

return UserStatUpdateSuccess

} catch(e: Exception) {

logger.error(e, "Failed to update user status for user ${payload.userId}")

return UserStatusUpdateFailure

}

}

}

class UserStatusUpdateOrchestrator(

private val userStatusManager: UserStatusManager,

private val userUpdatePublisher: KafkaPublisher<UserUpdateTopic>

) {

companion object {

val logger = logger()

}

fun performUserStatusUpdate(payload: UserStatusUpdatePayload) {

when (userStatusManager.updateUserStatus(payload)) {

is UserStatusUpdateFailure -> {

logger.error("Failed to orchestrate User status update for user ${payload.userId}")

}

is UserStatusUpdateSuccess -> performSideEffects()

}

}

private fun performSideEffects(payload: UserStatusUpdatePayload) {

userUpdatePublisher.publish(payload.toKafkaMessage())

}

}

a few good things have happened here:

- we ensure our

UserStatusManager.updateUserStatusfunction returns a newUserStatusUpdateResultsealed interface, which we implement only in a success or failure form - which means we get a compile time guarantee this part of the state machine is correctly defined and will never run into an unexpected state - in the orchestrator class, we operate on the

UserStatusUpdateResulttype with the when conditional operator (a state machine ready switch statement) to only perform the event publishing when the result is a success type - we haven't violated any of the earlier discussed benefits we get from using the orchestrator model - reusuability, independent testability, ease of maintenance

- we've gained even more confidence that at runtime, if something goes wrong, we know exactly what and exactly why

basically, by using the orchestrator model and sealed classes - we can see the future.

extra for experts

as an aside, there is one part of our finite state machine i intentionally did not represent in code. can you find it? if so, feel free to reach out and send me an updated code snippet hint: it might be related to event publishing